I’ve been avoiding writing this because as I think about it, some of it is – well – embarrassing. When you’re at the far end of life’s travels and you look back at the things you did when you were 20+, as much fun and exciting as they seemed then, they might be unseemly today. I’ll let you be the judge.

The story begins behind my desk in the offices of WWFM – the college radio station at Franklin and Marshall College where I was the News Director. I was reading my monthly copy of Broadcasting Magazine when I came across an article by the President of TVAR – the sales arm of Westinghouse Broadcasting. The article described the quality challenge commercial television was facing due to the rise of what we then called Educational TV. He cited opera, ballet, and theater productions being produced with quality and having the potential to tear audience from the mind numbing sitcoms and oh-so-predictable cop shows that were the mainstay of commercial TV.

Now, keep in mind that at this moment in my life, I was 20 years old, a junior at F&M, studying English Literature and I’d just completed a semester of Shakespeare with Professor Ed Brubaker, the director of the annual summertime Oregon Shakespeare Festival. (Click here for more info on Ed Brubaker.) Furthermore, I was the local TV anchorman on WLYH-TV’s (channel 15) Lancaster News. It was a CBS affiliate.

As I read the magazine article, an idea began to from very quickly. It rose like a mist and congealed in my head in seconds. I picked up the phone. Called information in Manhattan and got the phone number for TVAR. I called and asked for the president. He answered, “If you really believe what you wrote,” I said,” you’ll fund my plans for the definitive works of Shakespeare on commercial television.” Wow – where did that come from? And to my surprise, he invited me to New York to discuss how we might pursue such a project. We set a date, and I began planning.

First I called Brubaker. “Professor, I have a meeting in a couple of weeks with Westinghouse Broadcasting folks to talk about producing a series of Shakespeare’s works on commercial television. Would you be interested in directing?” He was interested.

Next, I called my parents and asked if they knew anyone with connections to top Shakespearean actors. I don’t know why I thought my mother, born in Brooklyn, and my dad an immigrant doctor from Poland, would have any clue about Shakespearean actors, but they actually did. They met a Russian Impresario at a dinner party in New York. They got his phone number for me. He invited me to lunch at the Russian Tea Room on 57th Street in Manhattan. (I had to pay.)

This guy was right out of central casting. Black cape, thick Russian accent, a bit rotund and he spoke and moved with a dramatic flair that impressed the 20-year-old me. After Borscht and Vodka (you could drink at 18 in New York in those days) he gave me the telephone number of Philip Burton – the director of the Academy of Musical and Dramatic Arts in New York. Philip Burton was Richard Burton’s step-father. And Richard Burton and his then-wife, Elizabeth Taylor, were both Shakespearean actors.

I called Mr. Burton at his home in Greenwich Village and explained that Westinghouse might fund my project – a television series of well-produced Shakespearean works. He asked me to bring a potential contract to his home so we could discuss his role as the theatrical producer of the whole deal. (I guess I was envisioning myself as the “Executive Producer.”)

But, I had a real problem. I was 20 years old and did not have a theatrical attorney on my staff at the college radio station or anywhere else. But my family’s lawyer, Harry Greenspan (Harry and Thelma Greenspan were family friends) was somebody I could call for advice. Harry protested that he knew nothing of theatrical law. I told him I was desperate because my meeting with Philip Burton was in a week, and oh, by the way, I won’t have any money to pay you Harry until the show gets underway. Harry was a prince. He studied up on theatrical law and created a contract that I brought with me to Philip Burton’s brownstone in the village.

He looked it over and said it was pretty useless, but I suggested we could work out all the details so long as he was willing to participate. I’d be glad to work with his attorneys to get it straight. To my surprise, he did not rebel at working with a 20-year-old kid.

The most important part of our meeting in Greenwich Village was his agreement to provide famous Shakespearean actors (depending on the available pay). The names we discussed were Hume Cronyn, Jessica Tandy, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. Now this was a list I could bring to my Westinghouse meeting!

When that day finally came, I was armed with Philip Burton’s tentative agreement, Ed Brubaker’s expression of interest, and lots and lots of Chutzpah located in a giant balloon just over my head. So, when I arrived for my meeting with the TVAR president, the first thing he did was burst the balloon. “You’re a kid.” POW! “But I have really big people working on this with me”, I said. “You’re a kid. Maybe we could work out some sort of internship for you, but nobody here is going to fund a project like this with a kid.” Ouch.

I went back to Lancaster and my desk at the college radio station. But I wasn’t ready to give up. I told my colleagues at the station what happened in New York. One of them, Michael – our radio station business manager, thought he could help. He lived on the same street in Scarsdale, NY (a wealthy Westchester County suburb of New York City) as Michael Dann, the senior vice-president of programs at CBS. “Mike Dann! You know Mike Dann?”, I screamed. Instantly I made the radio station business manager, Michael, a partner in this venture. At that very instant, my new partner picked up the phone, got Mike Dann’s home number from his parents, and called the broadcasting legend responsible for Lucy, Red Skelton, and countless other TV shows that made CBS the number one rated network in America. We had an appointment for the following week at ”Blackrock”, the CBS office building on West 52nd Street in Manhattan – an appointment on the 34th floor. (CBS had an altitudinal hierarchy at Blackrock. Senior vice-presidents were on 34. The president, Frank Stanton and his staff, occupied the entire 35th floor and William Paley the founder and chairman of CBS, occupied the entire 36th floor.) I was going to 34. That was like being very close to God.

When my new partner and I arrived at the building, we had to cross an American Federation of Television and Radio Artists picket line to get in. CBS was in re-runs as all the live and taped shows were cancelled due to the strike. (By an odd coincidence, 3 years later I would participate in turning WCAU-TVs newroom into an AFTRA organization. I’m still a member.)

When we finally made our way to the 34th floor, we were ushered into Mike Dann’s office. He was on the phone, fiercely shouting at a producer in Los Angeles. Red Skelton, it seems, had just been pulled off the set at Television City by union shop stewards who were enforcing the strike. It was a bad day to be making a proposal at CBS (A bad day at Blackrock, eh?). Nonetheless. Mike Dann was gracious and he organized a meeting with 5 of his vice-presidents. These were people who would go on to fabulous careers managing commercial television for decades. Among them was Fred Silverman who later ran Television City, and a fellow named Irwin Segelstein. who eventually moved on to NBC as their Executive VP for Programs.

Well, my partner Michael and I made a fabulous presentation. I thought so anyway. We rolled names like Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy off our tongues so glibly, how could they possible not fund the project. But in the end, it was just a fantasy of two 20-year-old kids playing big-time producers for a day in the big city. In the end, there was – zip, zilch, nada. Not even a phone call.

So, as April 1967 was rolling around and I was facing the coming end of my junior year in school, and a long summer as the anchorman of the WLYH-TV Lancaster News (oh god, spend the summer in Lancaster, Pennsylvania – a horrible thought for a kid from New York) I picked up the phone again. I called CBS in New York and asked for Irwin Segelstein. “Hi Irwin.” You can only call a CBS vice-president by his first name if you are 1, 20 years old, 2, not a CBS employee, and 3, the presumed personal friend of the vice-president’s boss – Michael Dann. “Of course, nothing ever happened with that Shakespeare thing, and while I’m working for the affiliate in Lancaster, I was wondering if there might be something I could do at CBS in New York this summer.” Mr. Segelstein was most anxious to do something for his bosses’ friend. I was setup with an appointment at CBS Facilities and Personnel to determine if I could become a management trainee. They gave me a whole battery of psychological tests and in the end concluded I had only one fault – too much ambition.

I was told that I was to become the first management trainee who did not have an MBA. I spent the summer at WCBS-TV performing studies of how network sports was eating into locally produced (and revenue producing) program time at WCBS (the network flagship station). I spent time running the stations’ operations and traffic departments while managers were on vacation. And at the end of the summer, I was promised an opportunity to continue on a management path when I graduated the following spring.

As my senior year was ending, I called my old boss at Facilities and Personnel and asked where I would start my new management position. We had already agreed I should work in news management and the options were to move me to bureaus around the world and see what positions I fit into best. So, I asked, is it London, Paris, Rome, Tel Aviv (all the places I was hoping for) and he replied, “have you seen our stock lately?” I had. It had dropped over the course of the year from the mid-$70 range to about $35. “We’ve had to cut a lot programs. The management trainee program is now open only to minorities.” “But, I’m Jewish,” I protested. “That doesn’t count anymore”, he replied. Oh.

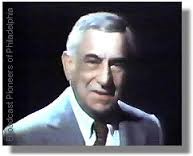

But he agreed to send my resume to the news directors of the 5 TV stations owned and operated by CBS, including WCAU-TV. During my senior year in school, I worked as a reporter and anchor for a powerful regional rock station, WSBA in York, PA. But I also called the assignment editor at WCAU-TV, a mere 75 miles from Lancaster, and told him I’d worked at CBS in New York as a trainee and if there was any news coverage I could assist with please, call me, as I was active covering stories every day. He explained the union situation at WCAU-TV would prevent my direct involvement but we’d keep in touch if there were stories I could assist with. Nothing came of that except, that when I called Frank “Skip” Oprendek, the assignment editor, in June of 1968 after school ended, he invited me to come to the station for an audition. I had already interviewed at WRGB-TV in Schenectady, New York, and was looking for an agent in New York to help me get a job. But when I arrived at WCAU-TV for my interview, Skip introduced me to Barry Nemcoff. Now, Nemcoff, in case you didn’t know it, was part of the Pottstown Mercury staff when it won a Pulitzer in the 1950s. He then went to work for Edward R. Murrow at CBS in New York and became one of Murrow’s boys. When Murrow went on to head the United States Information Agency at President Kennedy’s request, Nemcoff joined him and worked in the USIA office in Tokyo. He returned to CBS and Philadelphia in 1966. Nemcoff thought I looked like Bill Stewart (see my blog post on Bill) and while he had no openings on his staff, he agreed to send me out with their political reporter, Dan Cryor, to create a duplicate story of the one Dan was producing for that night’s show. I did it, and Nemcoff liked it. In fact, he was concerned that Cryor had missed the point of the story after seeing my version. But, still, there was no opening. “Would you hire me if there was an opening?” “Yes, I would, but I think you’re fishing for compliments”, he said. And once again that mist rose and congealed in my brain. “No”, I said, “I have an idea. Remember what you said – that you’d hire me if there was an opening.”

I left his office and walked down towards the basement exit where I’d seen a pay phone. I called my old boss at CBS Facilities and Personnel. “If you don’t provide Nemcoff with money to hire me until there’s an opening, I’m going to end up at WRGB in Schenectady (a General Electric owned TV station) and all the money you spent on me last summer will be wasted.” “Wait a few minutes,” my old boss said,” then go back to Nemcoff’s office.”

10 minutes later, I was working in the newsroom at WCAU-TV with a paycheck that came by mail from CBS in New York every week for 3 months until an opening occurred in Nemcoff’s budget.

And that’s how I got my job at WCAU-TV.